What is pneumococcal disease (PD)?

PD is an infection caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae (S. pneumoniae). PD may manifest as invasive and noninvasive disease. Invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) can result in serious illness.1

Pediatric populations remain at risk for PD. Pneumococcal infections are a leading cause of serious illness and cause substantial morbidity worldwide.1,2

How are pneumococcal bacteria spread?

Pneumococcal bacteria spread from person to person through contact with respiratory droplets.2

Risk of transmission increases with close personal contact, cold weather, and concomitant viral respiratory infections.3

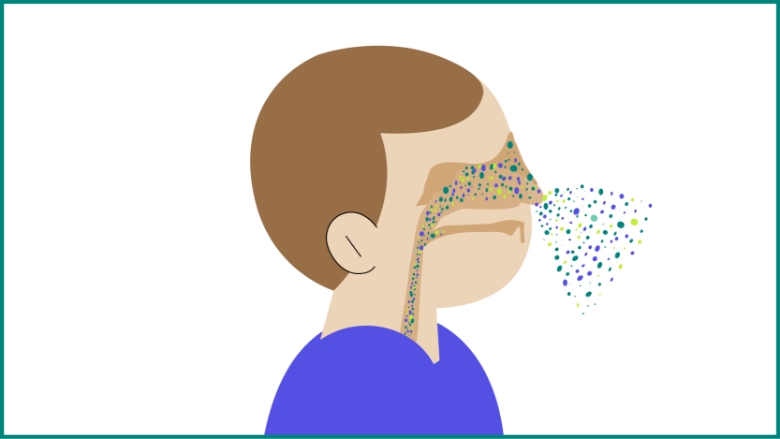

Pneumococci can colonize the nasopharyngeal cavities without causing illness, referred to as asymptomatic carriage.2

S. pneumoniae might further spread from the nasopharynx to other body sites or organs, such as the middle ear (acute otitis media) or the bronchi down to the lungs (nonbacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia).1

What are the clinical manifestations of noninvasive pneumococcal disease (PD)?

Noninvasive, or mucosal, infections include3:

Acute otitis media (AOM)

AOM, a middle ear infection frequently caused by S. pneumoniae, is one of the most common infectious diseases of childhood and is a major cause of morbidity and antibiotic usage.1,4

Nonbacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia

Pneumococci is the most common bacterial cause of childhood pneumonia, especially in children younger than age 5 years.3

What are the clinical manifestations of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD)?

Invasive infections occur when pneumococci invade a normally sterile site such as the bloodstream or brain, causing serious diseases such as bacteremia, pneumonia with bacteremia, or meningitis.2,3

Pneumococcal bacteremia

Pneumococcal bacteremia without a known site of infection has been shown to be the most common invasive clinical presentation among children younger than 2 years.3

Bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia/empyema

Bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia is another common manifestation of IPD in children aged 1–4 years.5

Pneumococcal meningitis

Pneumococcal meningitis is a manifestation of IPD in children younger than 5 years.3

Neurologic sequelae, such as behavioral disabilities, seizures, hearing loss, and motor deficits, can happen in as many as 50% of pneumococcal meningitis survivors.6,7,a

a Meningitis mortality and incidence according to pathogen over time (2000–2015) were analyzed using estimates produced by the WHO-MCEE pathogen model. WHO-MCEE, The World Health Organization and the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health’s Maternal and Child Epidemiology Estimation group’s Child Mortality Estimation.6

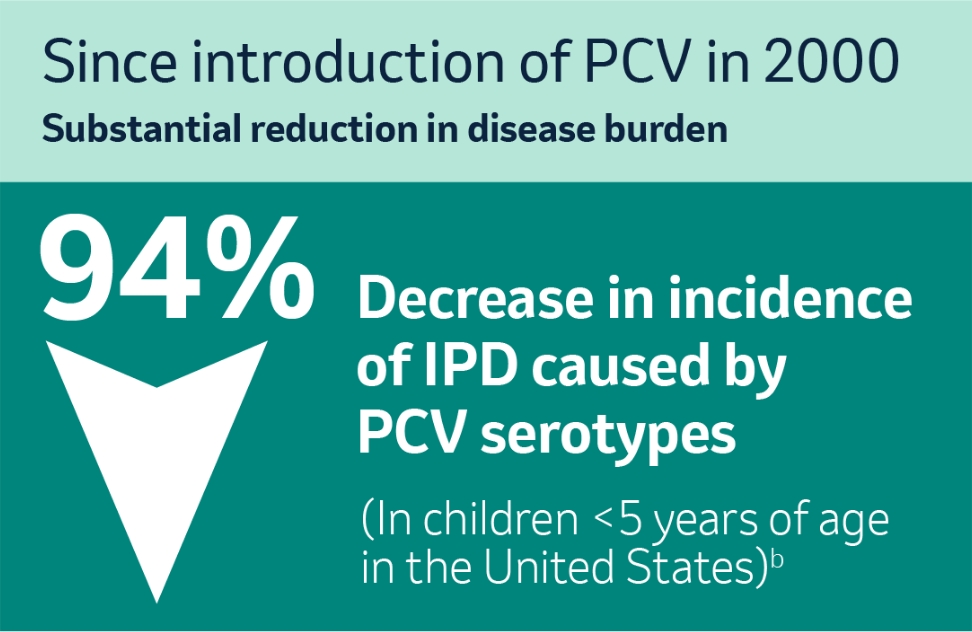

How have national pneumococcal immunization programs changed the epidemiology of IPD?

Studies from the US, which in 2000 was the first country to introduce a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PVC), have illustrated a substantial reduction in incidence of IPD caused by vaccine serotypes in children <5 years of age.2

b European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Fact sheet about pneumococcal disease. Accessed March 22, 2022.2

Which serotypes are the leading causes of IPD in infants and children?

While about 100 distinct serotypes have been identified to date, 20–30 show significant invasiveness in all humans.3,8

For example, in 2018, serotypes 3, 8, 10A, 12F, 19A, 23B, and 24F represented the most frequent serotypes of S. pneumoniae from confirmed cases of IPD in children younger than 5 years in Europe.5

Serotypes Responsible for Most IPD in Children <5 Years 5,c

c Based on the top 5 most frequent serotypes associated with IPD cases in children aged <1 years and 1−4 years in 2018. TESSy, The European Surveillance System.5

Furthermore, 22F and 33F are emerging as nonpneumococcal vaccine disease-causing serotypes among children <5 years internationally. Based on data from countries where pneumococcal vaccination programs have been introduced, 22F and 33F were common, causing 4% to 5% of childhood IPD cases in Europe.9,d

d Meta-analysis 2000–2015: Study evidence pooled had a focus on North America and Europe. Serotype prevalence and rank order varied by region.9

However, the prevalence of individual serotypes that cause IPD fluctuates across age groups, regions, and time.9

It is important to note that serotype 3 is a significant cause of IPD and has remained a leading cause of IPD among children younger than 5 years.5

What about serotype 3 and IPD?

Despite a decline in IPD, serotype 3 is a growing threat for your pediatric patients.5,10

When taking a closer look, serotype 3 increased in prevalence from 2014 to 2019 in Europe.10,e

e Data reported from the following countries: Austria, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom.5

While being included in pneumococcal vaccines, certain serotypes, such as 3 and 19A, continue to contribute to the IPD burden in children.5,f In fact, when comparing distribution in 2014 and 2018, there was a sharp increase in serotype 3.5

f Based on data for 2018 retrieved from TESSy on the top 5 most frequent serotypes associated with IPD cases in children <1 years and 1–4 years of age. TESSy, The European Surveillance System.5

g Based on an analysis of serotype 3 from 2014 to 2018 identified through the ECDC’s surveillance data. ECDC, European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.5

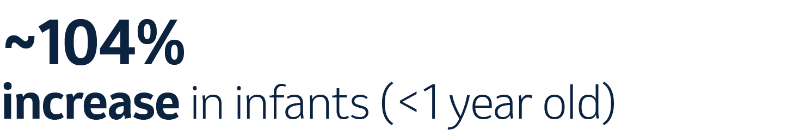

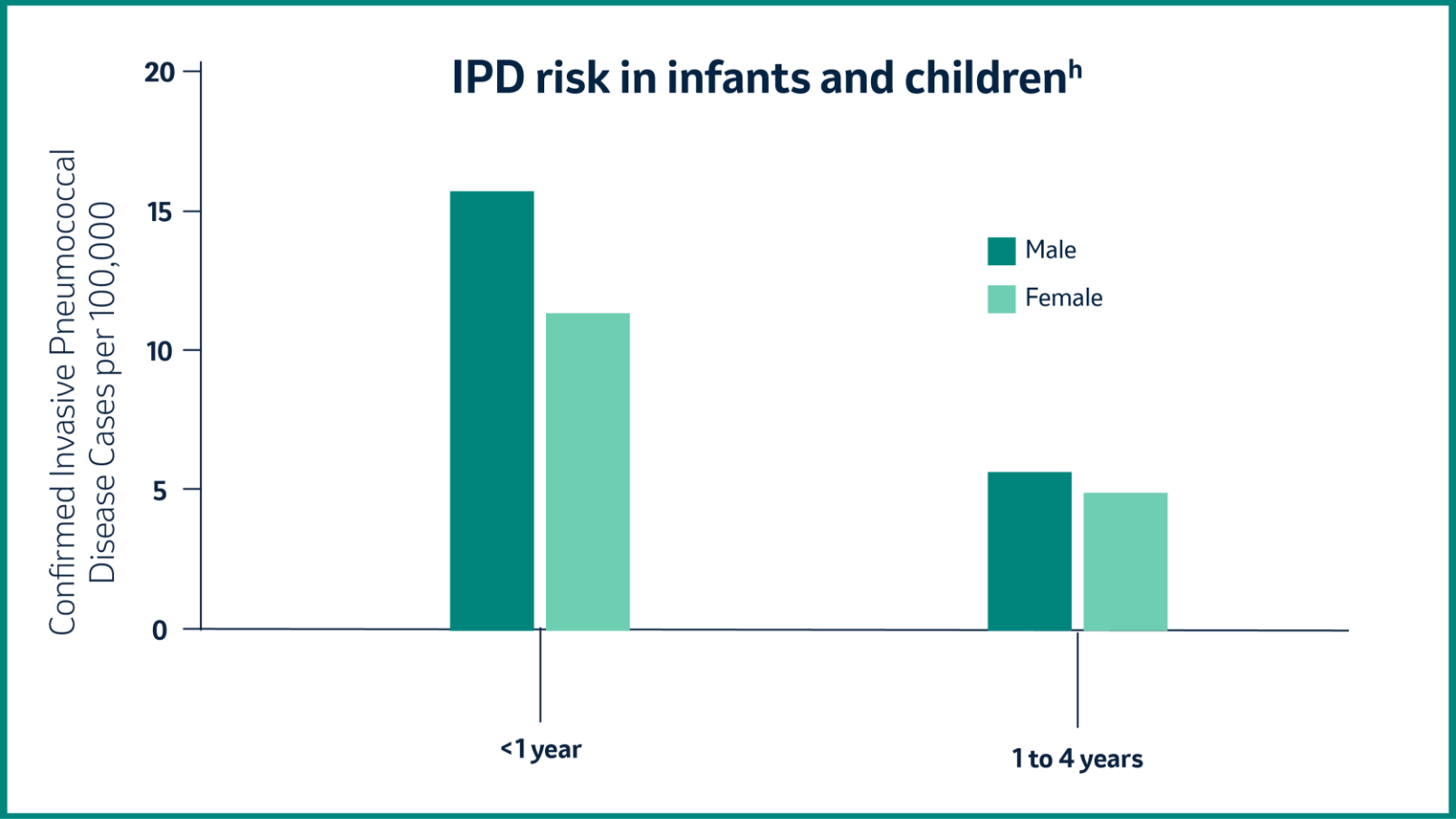

Which age group has the highest risk of IPD?

In 2018, children younger than 5 years had an increased risk for IPD, while the incidence of IPD was highest among infants younger than 1 year.5

Pneumonia ranked as the 2nd leading cause of death in Malaysia in 2022.11

h Based on data for 2018 retrieved from TESSy on 11 March 2020. TESSy, The European Surveillance System.5

© European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), 2020. Reproduction is authorized, provided the source is acknowledged.

What are the factors that increase risk for IPD in infants, children, and adolescents?

Children with certain underlying conditions are at increased risk for pneumococcal disease.12,i

Chronic Lung Disease

~ 3X RISK

Chronic Liver Disease

~ 11X RISK

Asplenia (absence of spleen)

~ 48X RISK

Disease of White Blood Cells

~ 50X RISK

Chronic Heart Disease

~ 6X RISK

Cochlear Implant

~ 20X RISK

lmmunocompromising Conditions

~ 22X RISK

iRisk for invasive pneumococcal disease in children age <18 years relative to healthy counterparts.

So why is greater awareness of pneumococcal disease in infants and children needed?

Infants under 2 years have the highest risk for developing invasive disease.2 The serious threat of IPD calls for increased attention and priority for our youngest populations.1,2

References:

- World Health Organization. Pneumococcal Disease. Accessed May 24, 2022. https://www.who.int/teams/immunization-vaccines-and-biologicals/diseases/pneumonia.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Fact sheet about pneumococcal disease. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/pneumococcal-disease/facts.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases, The Pink Book: Course Textbook, 14th Edition. Chapter 17, Pneumococcal Disease. Available From: https://www.cdc.gov/pinkbook/hcp/table-of-contents/chapter-17-pneumococcal-disease.html?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/pneumo.html. Last Accessed: 1 August 2024.

- Liese JG, Silfverdal SA, Giaquinto C, et al. Incidence and clinical presentation of acute otitis media in children aged <6 years in European medical practices. Epidemiol Infect. 2014;142(8):1778-88. doi:10.1017/S0950268813002744. Erratum in: Epidemiol Infect. 2015;143(7):1566.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Introduction to the Annual Epidemiological Report. In: ECDC. Annual epidemiological report for 2018 [Internet]. Stockholm: ECDC; 2018. Accessed May 24, 2022. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/invasive-pneumococcal-disease-annual-epidemiological-report-2018.

- Wright C, Blake N, Glennie L, et al. The global burden of meningitis in children: challenges with interpreting global health estimates. Microorganisms. 2021;9(2):377. doi:10.3390 microorganisms9020377.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pneumococcal disease. Clinical features. Page last reviewed January 27, 2022. Accessed August 8, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/pneumococcal/hcp/clinical-signs/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/pneumococcal/clinicians/clinical-features.html.

- Geno KA, Gilbert GL, Song JY, et al. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28(3):871-899. doi:10.1128/CMR.00024-15. Erratum in: Clin Microbiol Rev. 2020;34(2).

- Balsells E, Guillot L, Nair H, Kyaw MH. Serotype distribution of Streptococcus pneumoniae causing invasive disease in children in the post-PCV era: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):e0177113. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177113.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Surveillance Atlas of Infectious Diseases. Accessed May 24, 2022. https://atlas.ecdc.europa.eu/public/index.aspx.

- Department of Statistics Malaysia. Statistics on Causes of Death, Malaysia, 2023. Available From: https://www.dosm.gov.my/portal-main/release-content/statistics-on-causes-of-death-malaysia-2023. Last Accessed: 17 April 2024.

- Weycker D, Farkouh RA, Strutton DR, et al. Rates and costs of invasive pneumococcal disease and pneumonia in persons with underlying medical conditions. BMC Health Ser Res. 2016;16:1-10. doi:10.1186/s12913-016-1432-4.

MY-PVC-00107 AUG/2024